Electoral Synchronisation Risk: Decision Latency in Coalition Systems

Electoral Synchronisation Risk (ESR) is a system-level framework for analysing how overlapping election cycles and leadership transitions across allied democracies can temporarily increase coalition strategic decision latency in fast-moving security crises. The claim isn’t that democracies “fail” or militaries go offline — it’s that authorisation and alignment slow down when multiple political calendars collide.

Most security analysis is obsessed with hardware: ships, missiles, basing, inventory, production rates. ESR is about something subtler (and more annoying): the political time constant of a coalition. When crises move faster than the coalition’s ability to authorise escalation-capable responses, timing itself becomes a risk mechanism.

1. What ESR actually is (and what it isn’t)

2. The key distinction: continuity vs permission

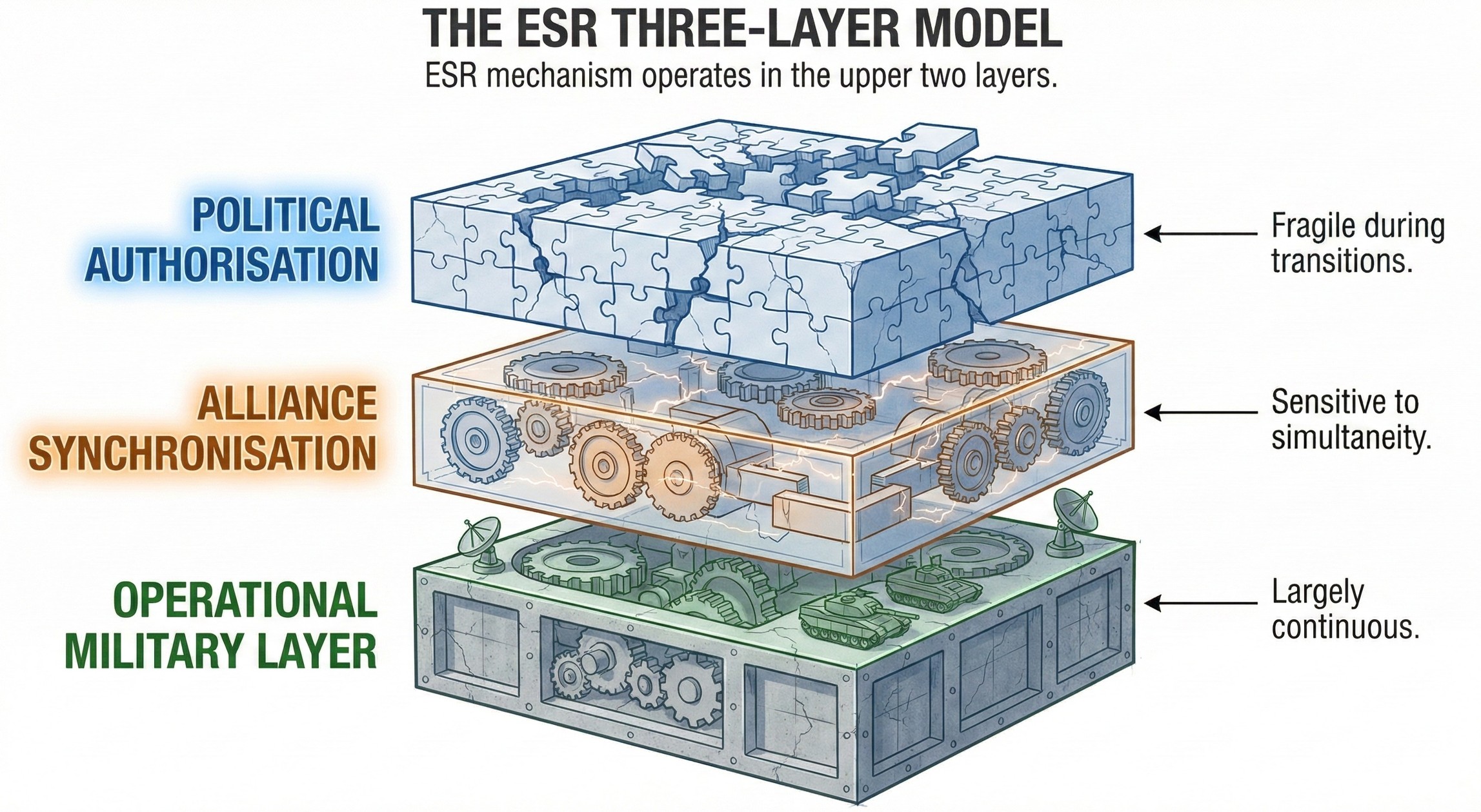

The most common objection is the “institutional continuity” argument: militaries and intelligence communities operate regardless of elections. True — and incomplete.

Two layers, two clocks

Kinetic Readiness (largely constant): standing defence plans, intelligence collection, tactical self-defence, pre-authorised ROE.

Escalatory Permission (variable): horizontal escalation, reserve mobilisation, multi-lateral sanctions, alliance-binding commitments — all requiring fresh political authorisation.

Elections don’t remove legal authority to act, but they compress the political tolerance for decisions that move beyond the status quo. In ESR terms: the “hardware” is on, but the “permissioning” layer gets sluggish.

3. A practical proxy: Coalition Strategic Decision Latency (CSDL)

To ground the concept, the paper introduces Coalition Strategic Decision Latency (CSDL): the elapsed time required for a multi-state coalition to grant escalation-capable permission beyond standing authorities.

4. The asymmetry problem: fragmentation vs consolidation

ESR is structurally asymmetric. Democratic coalitions have visible, frequent leadership transitions; counterparts may have longer periods of leadership continuity or centralised consolidation. That can create a temporary divergence:

- Democratic fragmentation: mandate-seeking, cabinet-forming, domestically constrained signalling.

- Authoritarian consolidation: lower internal friction and potentially faster escalatory authorisation.

This isn’t a moral claim and it’s not a prediction of behaviour. It’s a timing divergence: the decision delta between systems can widen at specific moments.

5. Why this is portable beyond the Indo-Pacific

The Indo-Pacific is used as an illustrative application, but ESR is not region-specific. It applies wherever:

- credible response requires coalition action;

- escalation-capable decisions require political authorisation;

- multiple coalition members are in simultaneous transition windows.

Plain English takeaway

Early action is easiest when others are still deciding — and hardest once they’ve aligned.

6. How to use ESR without becoming a doom merchant

ESR is useful as a calendar-aware stress test for coalition decision systems. It suggests very specific, non-hysterical questions:

- Which actions are covered by standing authorities vs requiring new political permission?

- What pre-authorisations (or delegated authorities) reduce the “permission gap” in high-ESR windows?

- Where are the coalition’s slowest veto points — and can they be pre-solved?

- How does signalling coherence change during campaign periods?

7. Closing

ESR doesn’t claim coalitions are weak. It claims that timing can become a mechanism — and it’s measurable enough to take seriously, model, and mitigate before hindsight shows you the pattern in high definition.